I never intended on visiting Zanzibar. Only when a music promoter friend in Nairobi casually mentioned that a world-class African music festival would occur on the island the following month (February,) did I even bother looking at the it on a map. Now, like my Euro-American counterparts of old (“Dr. Livingstone, I presume?”) I am stuck on this island longer than expected, and stewing amidst the humidity, the smells (both stinking and delicate,) and the dizzying menagerie of cultures that makes Zanzibar distinct, beautiful and deeply significant.

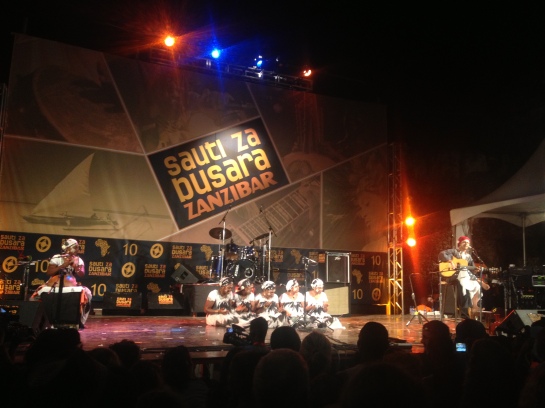

After a brief period of research, and upon securing myself an accredited press pass, I set my course for Zanzibar, ready to experience the 10th annual Sauti za Busara festival, called by some as “the friendliest festival in the word.” While this claim seemed to me both hyperbolic and immeasurable in any sense, I was still excited to see some great music in an amazing place. What particularly excited me was the prospect of seeing Malian diva Khaira Arby, whose native home of Timbuktu was, at that moment, being invaded by the French military in order to oust a brutal Al-Qaida affiliated militia which had invaded the region nearly a year ago.

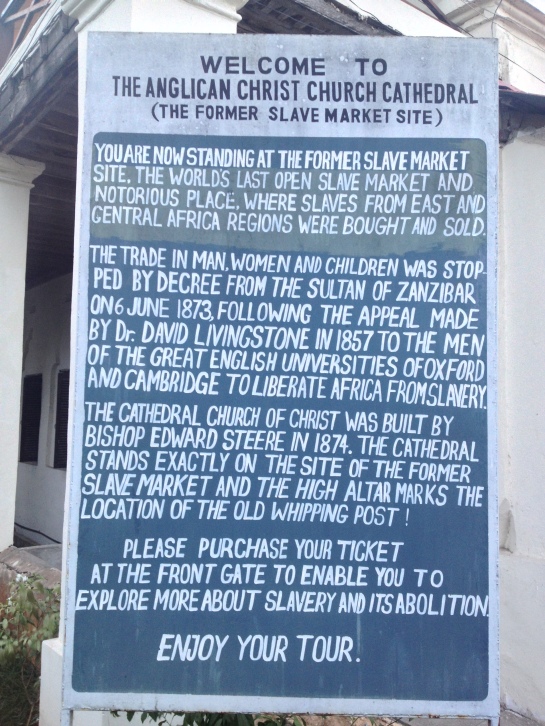

All of this, coupled with a basic knowledge of Zanzibar’s history, made my visit both enticing and meaningful. After all, it seemed utterly amazing to me that a Pan-African music festival would be taking place on an island which, two-hundred years ago, was the dismal epicenter of the Arab slave trade, a brutal enterprise that lasted well into the 19th century. Zanzibar can also be seen as the first departure point for Western colonial forces in East and Central Africa, both literally and metaphorically. America was actually the first Western power to establish a consulate here in 1839, when the island was still governed by the Sultanate of Oman. The Omanis dominated this strategic island for at least five centuries beforehand, and were then succeeded by the British, who claimed the island as a protectorate in the late 19th century. Prior to the Omani occupation, Shirazi Persians had influenced the Island, as well as Indian merchants. All in all, Zanzibar had been a center for trade and cultural exchange, as well as abhorrent human trafficking, for nearly two thousand years. In an odd way it was the perfect place for a peaceful celebration of African music, culture and identity.

Let me preface by saying that I consider myself extremely spoiled when it comes to music festivals. Hailing from the Pacific Northwest of the US (a region we call Cascadia,) my experience with festival culture has been profound- life changing, to say the least; blessed by a strong community of creatively potent, intelligent, and conscious people who groove to the most cutting edge music and art that Western counter-culture can muster- all the while trying to minimize our impact on the earth. In short, I have high standards for festivals. That said, I entered Sauti za Busara with an open mind and a deep love of African music.

Taking place in Zanzibar’s iconic Old Fort, an antiquated fortress with massive, barrel-like towers standing at its four corners, the venue was, quite simply, awesome. A square, grassy field, contained within the fort’s high walls provided a straight-forward area from which to dance, drink, and festivalize. Outside this area, but still inside the massive fort, was a large stone amphitheater that would serve as an arena for screening select documentary films, as well as an open avenue housing several curio shops selling cheap African wares. There was another bar at the far end, clearly a high-priced watering hole for tourists during the off-season. There were also no emergency services, hydration zones, or medical areas to speak of, and only two small bathrooms (one for each gender) which were to accommodate several thousand people, but hey, lets just disregard that.

Attending the pre-festival press conference, I had a chance to both meet and listen to UK-based festival director and DJ Yusuf Mahmod speak. Starting from humble roots, this festival, like many, grew because a dedicated crew of inspired people had a vision, and a love for Zanzibar, and Africa. They were also committed to promoting live music, a principle that was music to my ears after traveling for weeks and hearing only Hip-Hoppified African music such as Tanzanian Bongo Flavor, a painfully unoriginal style of autotuned R&B that poorly mimics what people must hear coming out of American media. “We believe that we have a responsibility to opening people’s minds to the importance of playing instruments, live,” Yusuf said, a refreshing conviction to say the least.

Yet this emphasis on live music was not without its critics. I heard many people, both black and white, complain that the festival lacked local Tanzanian talent, and that the event was primarily catering to mzungus, or white foreigners. One German girl, an intellectual aid-worker type I met at a beach-side bar after the festival, was actually upset there was no Bongo Flavor music, a concern I couldn’t help but scoff at. “But Busara only promotes live music,” I explained, discussing the importance of playing real instruments as well as the continuation of African musical traditions. “Well that’s not what the youth are listening to today,” she replied haughtily. “They should at least promote what’s popular in the area.” “Not if it’s bad music,” I said. In fact, in 2012, the Zanzibar International Film Festival (ZIFF) did feature a well known Bongo Flavor artist. He had never even performed his own music, having only recorded it in the studio, followed immediately by dancing in a blinged-out music video. According to a friend who helped produce and emcee the ZIFF festival, the “performance” failed utterly. “Personally, I don’t know how these Bongo Flavor artists can be considered legitimate musicians, especially on a continent full of masters,” I said. “Yea, but the crowd loved it!”

The crowd at Busara was an amiable mixture of international backpackers, adventurous families and lost-looking vacationers with awkward hats. On the local front, there was a collection of out-of-place Masaai men, adorned with traditional jewelry and accessories, their ubiquitous red cloths a reminder of the distant savannah that was a mere memory in this tropical paradise. There were modern-looking, well dressed African men and women, many from capital cities on the mainland, presumably Dar es Salaam and Nairobi, a majority of whom were there on some professional basis. And there was a large contingent of friendly Zanzibari Rastas, most of them admittedly “fishing” for pretty white women.

In fact, I could not help but notice the profusion of single white women, mostly between the ages of thirty and fifty, who seemed to be equally as eager to find themselves a nice young African man for the evening, or week. Eventually the obligatory courting rituals became a laughable facade after the three days of the festival, and in the end, I could not help but silently chuckle to myself at the sight of a young, dreadlocked Zanzibari man being taken out to a fancy restaurant by an older white woman (or two.) I had to wonder, who had the upper hand in these exotic rendezvous’? Was there some post-colonial and racial subtext, some subconscious notion of foreign extraction at work that only I could decipher due to my arduous background in political anthropology? Or were they, despite my cynical misgivings, honest, egalitarian affairs? The festival is about “intercultural exchange,” after all…

Throughout the festival, I never once felt overwhelmed. Usually I consider this a good thing, but knowing how madness and confusion can sometimes be the most fertile grounds for meaningful and transformative experiences, especially in the liminal realms of festopia, I found the absence of such conditions at Busara to place the festival in a tame sphere that bordered on the mundane. For some reason, perhaps due to the low volume of the soundsystem, perhaps due to a general creative lackluster that seemed to pervade amongst some of the artists, I never really found myself dancing. Nor did I find many others lost in a blissful frenzy. Ok, I did not expect Burning Man, but I did expect music loud enough to make a crowd full of people shake it. I expected to feel immersed in the vocals and delicate melodies of the Kora and African guitar. I wanted to be smacked in the face by the sound of the Djembe, compelling me and everyone nearby to dance, hard! Instead I found heads nodding lazily to the beat, occasionally taking sips from somewhat cold bottles of beer, shuffling back and fourth.

With regards to the artists, I heard several people describe the majority of the lineup as “money-savers.” It was made clear from the press conference that the festival was having a difficult time securing funding and sponsorships. At one point during the first night, after the clumsy self-congratulatory “We did it!” speech/dance, someone from the festival’s board of directors came on stage and gave a disjointed, emotional address about how they need more support from the Zanzibar business community. I found this appeal to be pretty disgraceful, both in its delivery and in its timing. A valid concern worth addressing in the proper setting, yes, but not so important as to disrupt forty minutes of music programming and use the stage as a soap box to voice your financial problems to a captive, paying audience.

That said, there were some genuinely good artists present. Nawal & Les Femmes de la Lune, an all female band from the Comoros Islands, was enthralling, though unfortunately cut short because of the unforeseen announcements and “speeches.” The act which moved me more than any others was by far the Kora duo of Sousou & Maher Sissoko. The husband and wife team, from Senegal and Sweden, respectively, evoked a palpable sense of love throughout their performance, exchanging sweet glances to each other with a stage presence that was simply magnetic. Other highlights included Atongo Zimba, from Ghana, and of course, Northern Malian singer Khaira Arby, whose presence I felt was particularly important due to her exile and Mali’s current state of emergency resulting in international alarm.

Throughout the first two days of the festival, the emcees would continually remind people to not miss Cheikh Lo, the headling act from Senegal who was to play on Sunday night. This always struck a nerve in me, because it presumed that this artist’s presence was somehow more meaningful simply because of his higher price tag. ‘We paid the most for him, so make sure not to miss it!’ Cheikh Lo’s performance was mildly entertaining at best, certainly not worth more than any of the other artists. Not until right before her set (and this was upon her request,) did anyone deem it important to mention the crisis in Mali- the fact that at this moment, a battle was taking place in the artist’s home town, and that not even a year ago, Khaira Arby was forced to flee her home, fearing for her life, along with countless other Malian musicians, because the extremist force which had overrun their town had violently outlawed music.

Sauti za Busara, Swahili for “sounds of wisdom,” is not a bad festival by any means. In fact, it is an amazing festival that anyone should feel blessed and excited to attend. I may even come back, if I have the chance. The diversity of people, music, and scenery is truly an experience to behold. And it is an extremely friendly festival (maybe too friendly, if you are a single white women between the ages of twenty and fifty.) However, if this festival wishes to continue being know as the best music festival in East Africa, it may pay off to spend some time getting back in touch with the meaning behind the word “busara.” Otherwise if they are not careful, they may end up confusing it with a similar, but very different Swahili word: “biashara,” or, “business.”

What a self-righteous, pompous, patronising, self-congratulatory, irrelevant piece of nonsense and a waste of a press-pass on someone who cannot keep his cultural irrelevance in check…The writer is a sewage pipe of facts without any real understand of place…Busara, despite its challenges, will rock on without you as will the rest of Africa with its own music and expression, without reference to you for taste…

“intellectual aid worker” cf rampant sex starved European female sex tourist?

You should let Yusuf know that he is no longer based in Africa..

Zanzibar smells no worse than Paris on a good day…but it is nice to judge Africa…

Psssssst…your prejudice is showing…It is a total shame that this appears in the context of a project like Baba intended to do exactly the opposite.

Zanzibar, Busara and Baba should demand an apology…

@Shinga– I appreciate your passionate response, and apologize if this article offended you. If you read through the whole article, then you will know that this piece is not a condemnation of Sauti za Busara (or Zanzibar) by any means. Rather, this article contains (only a fraction) of the things that were witnessed and observed during the festival. Things like sights, smells, and venue details paint a picture of the event and the place for people who were not there, and who are not from there, more importantly. Things like foreign women coming to Zanzibar for a spicy island holiday, if you get my drift, seems to be an unspoken trend that I feel is part of this festival’s “shadow side,” but not necessarily a bad thing. We all have a shadow. Better to be aware of it then just pretend it does not exist. But to each their own…

I do wish you were a little more specific about your complaints… While calling the author a “sewage pipe of facts” does succeed as a good laugh, it does not help anyone move forward or attain any “real understanding of the place.” Perhaps you could offer some?

Thanks for sharing your experiences with us Simon. I appreciated your critique of the festival as well as the context you provided for the reader. It is easy to be unaware of events such as those happening in Mali, so thanks for filling in those of us that were previously unaware. Keep exploring, having fun and staying safe!

I am not a political correctness junky but there are a few observations I made too in the article which highlight Shinga’s concerns. I too was at the festival for the first time and it holds true that the low festival volume and the drama of sex tourism epitomise the shadow side of the festival but if we believe in freedoms, and only adults are involved, then it takes two to tango and let the music play. To cut to the chase, i quote three specific statements and pose questions. 1. “Let me preface by saying that I consider myself extremely spoiled when it comes to music festivals. Hailing from the Pacific Northwest of the US (a region we call Cascadia,) my experience with festival culture has been profound- life changing, to say the least; blessed by a strong community of creatively potent, intelligent, and conscious people who groove to the most cutting edge music and art that Western counter-culture can muster- all the while trying to minimize our impact on the earth” Q..ALL THIS GOOD STUFF IS COMPARED TO WHAT OR WHO?

2. “one German girl, an intellectual aid-worker type I met at a beach-side bar after the festival” Q WHY IS THERE NO REFERENCE TO INTELLECT ON THE PART OF AFRICANS, APART FROM BEING MORDEN LOOKING? 3. “On the local front, there was a collection of out-of-place Masaai men, adorned with traditional jewellery and accessories, their ubiquitous red cloths a reminder of the distant savannah that was a mere memory in this tropical paradise” Q..WHY WOULD THE BEAUTIFULLY DRESSED MASAI MEN BE “OUT-OF-PLACE” ON A CONTINENT AND REGION THAT THEY HAVE BEEN WANDERING FOR MILLENNIA WHILE EVERYONE ELSE (INCLUDING DRUNK AND SKIMPY DRESSED EUROPEANS IN A 99% MUSLIM ISLAND) WOULD LOOK “NORMAL”. While we bring our superior education and experience to the places we visit, like Dr Livingstone, we will not get everything right so if you had asked any Zanzibari, they would have told you that the “out-of-place” Masai men were part of the local security, and that would have explained the minimal uniformed police presence.

Hi Tawanda– Thanks for your comment.

For the sake of time, I’ll address the specific questions you posed.

1) ‘All this good stuff’ regarding festival culture is to illustrate my background and orientation regarding music festivals- where I come from, what I expect, and what I know is possible in a festival atmosphere. It’s to frame my own observations, and therefore biases- an attempt to be transparent.

2) ‘Intellectual aid worker type’ is code for a foreign and ultimately PATERNALISTIC mentality in Africa, one of Aid/NGO/Development work, and neo-liberal sensibilities that covertly say “I as a white, educated foreigner know what is best for Africa, and for Africans.” This is a perspective and unconscious cultural practice that I detest. I met plenty of intellectual and inspiring Africans at this festival, some of whom are now friends. I mentioned this encounter to illustrate this perspective that is quite common amidst “Intellectual Aid Worker Types,” people that can be found around Africa that now constitutes its own culture. To put it bluntly, Bongo Flavor music is bad, my opinion. Just because it is popular with Tanzania’s youth does not mean it should be promoted by a festival meant to promote live music and traditional culture. There is nothing politically incorrect about saying, “Sorry, I think this music is terrible, and if Tanzanians keep trying to regurgitate what they see coming out of American media they are going to lose their OWN culture and therefore future.” It’s OK to say the music sucks, even if its popular with the African people you (as an Aid worker) are trying to change…

3) The Masai, while beautifully dressed, did seem out of place to me, and with many other Zanzibari’s I spoke with. The Masai, as a profoundly land-based pastoralist group from the savannahs of northwest Tanzania and southwest Kenya, have about as much in common with the ocean/beach as a fish does with a bicycle. Masai on the beach with neon pink stunner shades speaking Italian. One of those bizarre sights that reminds you, “yes, this is the 21st century.” This notion was pointed out to me by local Zanzibari friends, confirming the weirdness of it. If they were local security, they did a great job, as far as I could tell.

Again, I appreciate your response and thoughtful questions.

I ‘silently chuckle’ at your interpretation of the festival goers carnal intermingling – especially from someone who has been to Burning Man. Instead of wondering who had the ‘upper hand’ in our neo-liberal, western-globalized world, I viewed the unfolding relationships you write of as an bold example of women and men doing their part to create a sustainable and peaceful world by communicating love and understanding around the world. What better way to propagate peace? Travel to a foreign land, engage in the people who wish to engage with you, and then break down the barriers of race and sexism by sharing the divine feminine understanding of our humanness? I do hope Sauti za Busara is sponsored to provide free and widely available condoms for all interested in participating in the love-festival. And really, who knows – the ladies at dinner with the gentleman could have been working on a ‘biashara’ deal to fund more toilets and first aid stations at next year’s festival.

I am amazed at how much flack you’re receiving for your views on Sauti za Busara 2013. I am a Tanzanian, resident in Dar es Salaam, and Sauti za Busara 2013 was the first time I attended the festival. My thoughts were very much in line with yours. Great piece! 🙂